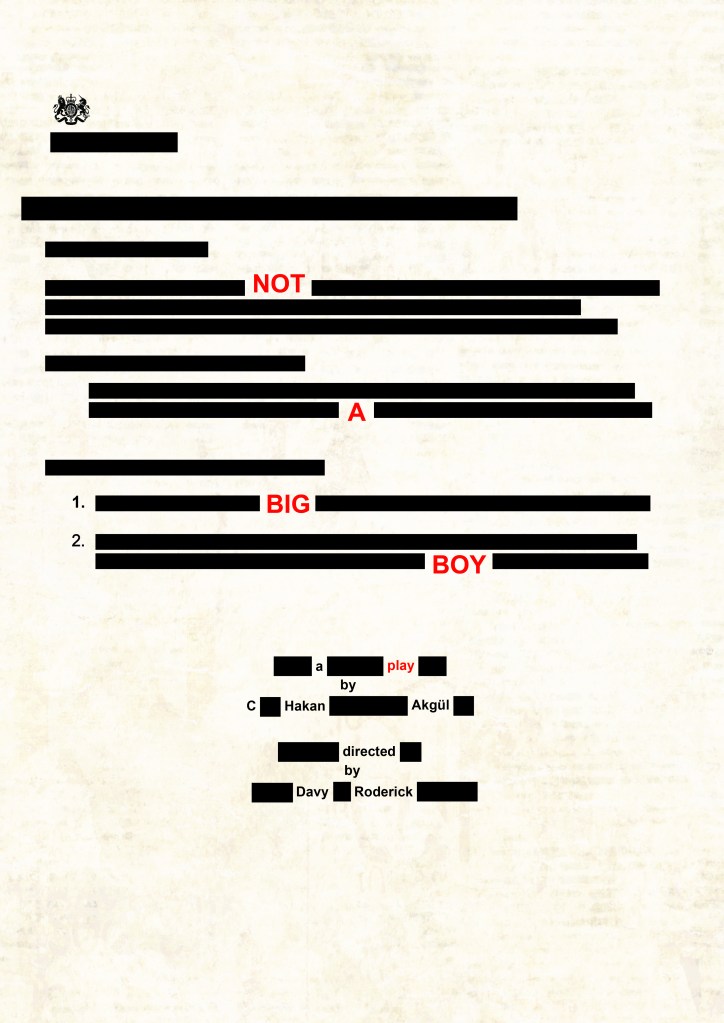

C Hakan Akgül is Not a Big Boy

Yoghurt has more culture than you

It’s emblazoned on a sign held up by Kerim, a man on a rant about the injustice that the word ‘Greek’ is attached to yoghurt pots in shops across the UK.

It’s one of the many laughs in Not a Big Boy, a one-man production for London’s Drayton Arms theatre, telling the story of a Turkish-born frozen yogurt salesman living in London. Kerim battles immigration procedures from a terribly designed chair in the visa centre, balancing humour and heart-rending poignancy with a captivating ease.

Writer and performer C Hakan Akgül., feels as strongly about yogurt as the protagonist he plays on stage.

‘I wouldn’t even give them (the Greeks) shared custody… we invented it!’

Akgül’s passion matches the protagonists that he plays, but that is where the heated anger ends. At all other times in the story, Kerim is cautious and polite as he tells us of his larger-than-life mother and his stories from a childhood in Turkey. Infuriating immigration paperwork is a jumping off point for the production, but Akgül’s script has a wonderful ability to meander through universally felt topics of grief and self-worth, hitting humour when it’s needed and emotion too.

Davy Roderick’s direction keeps Kerim mostly confined to the small circle around the chair in the visa centre, so the text isn’t allowed to hide behind complicated stage management or music. The choices are simple, and the resulting effect manages to hold a captivating nuance in a way so many one-person shows fail to.

The final manifestation of Not a Good Boy has been a long time in the making. The show had its first life as a shorter version written in Turkish based on article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights, premiering at Turkey’s biggest international theatre festival in 2023.

Producing a final full-length production on London’s theatre scene was motivated in two parts for the team: its strength as show, but also Akgül’s need, ironically, for a visa.

Before applying to an MA course in London, Akgül hadn’t written a play in English, or for a British audience.

I felt I needed to write something that would fit a certain budget, or fit the BBC, or something they’re looking for…When I tried to do it that way, it didn’t work. When I try to do it my way, it doesn’t work most of the time either. But at least, sometimes, it does… “

Translating and extending the text for a British audience was transformative to the text itself.

Some things were funny to the British audience that I didn’t expect. Like going to my cousin’s circumcision. “

In a joke that mocks suicide bombers and friction between Turks and Syrians, Akgül found a British audience to be suddenly very cautious.

I realised I needed to approach the joke in a more approachable way so they can laugh, so they’re not scared to laugh. “

Approachability was another hurdle Akgül found during adaptation.

‘When I started realising how many times I had to translate things or change the phrasing or meaning to accommodate an audience that are not familiar with the culture, I realised there was a new theme into the play. I was othering the audience a lot, I was explaining a problem in a foreign language, a problem in a foreign culture to them. “

This notion provides lots of the jokes: about Turkish swear words featuring midwives, and the British favouring a muttering of ‘fucking hell’. But it also provides some of the most meaningful moments. Akgül’s texts takes an interesting turn to Turkish folklore icon Nasraddin Hodja and his witty didactic tales. It is through this layered story telling that profoundly moving and subtle depiction of grief that plays on this very idea of othering and culture itself.

I realised grief is very personal, and that in a way is also othering. You’re in a culture of your own. So I combined both. “

AlthoughAkgül is not typically an actor, he is a D&D (Dungeons and Dragons) champion (not that D&D has winners and losers in the conventional sense). This is perhaps where his free and uninhibited stage presence that blends so well to Kerim’s characterisation in Not A Good Boy comes from.

Akgül is co-producer of Kafa20, a group of theatre-makers in many locations around the world, telling a D&D story full of mischief and high drama, streamed on YouTube and Twitch, and lead by Akgül as the main storyteller.

Further than an online format, Kafa20 is a creative platform for people to come together and tell stories through a variety of table-top RPGs. It is this part structured, part improvised and reactive storytelling that Akgül plans to take into future writing projects.

I want to try something much more interactive…there are some things that I find are in my wheelhouse, including making up stories on the go, adjusting the changes whilst sticking to the plot. “

Whatever form, and if Not a Good Boy is anything to go by, it is clear C Hakan Akgül’s future has something new and exciting to offer.

Promising young creative…

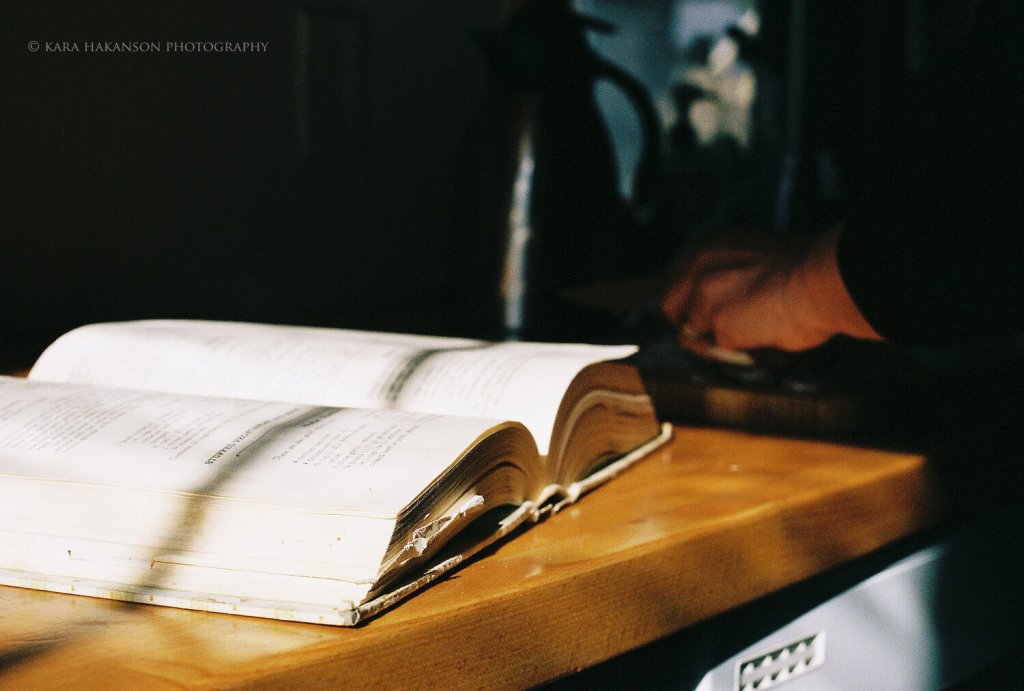

Photographer Kara Hakanson on her work, life, and the visa application process as a stimulus, or dampener on creativity…

‘To be fair, my life has been put on hold for this visa…’

Kara Hakanson suddenly finds herself wading through British bureaucracy to prove the worth of her artistic talent.

Photographer, Actor, Director (she wears too many hats to mention) Kara came to the UK at the end of 2019, and after a yearlong COVID based blip, she graduated from Drama Centre London in 2022 and has been working as a multi-faceted creative for two years since.

Now, Kara has to document her achievements to prove herself to be a ‘potential leader’ in her field of work, something that will be judged by Arts Council England as part of the Global Talent Visa.

Aside from the paperwork, I’m interested in how this effects Kara creatively. She appreciates how the admin side of things has forced her to reflect:

‘On the one hand it’s been oddly nice going back and documenting what I’ve done…’

‘On the other hand, it’s strange to have to prove to someone I have ‘exceptional promise’ in a field that’s so subjective.’

Subjective, perhaps. But I think from any angle, Kara’s visual work is particularly striking.

Titling a collection of photos Minnesconsin, Kara takes pride in the perspective her small-town upbringing brings her art, living on the border of Wisconsin and Minnesota and bounding between both when she returns to visit.

On a domestic level there is a particular play on light, on home comforts that seem alive in her US based work, and with it a forensic, yet playful intimacy.

She is able to capture suggestive moments, for example, capturing a protest whilst working with Patagonia.

‘I like to capture the emotion I am feeling.’

There’s a particular sweet quaintness to her ‘England’ photos, and some from her European travels as well. To me it spells out an emotional difference in each location.

‘Light influences my work a lot, so the different seasons in each location really affects that. In the UK there’s always green, but Wisconsin in the depths of Winter, it’s completely different.’

Kara agrees on my assessment of the differences between each location, but she’s suddenly taken aback –

‘It’s interesting you say that, now I’m thinking about the images…two very similar photos of a bedroom of the afternoon light, they’re kind of saying the same thing. But they’re completely different parts of the world.’

Kara shoots on 35mm, in homage to her dad.

‘I always called him the family paparazzi…(but) when he started switching to digital that’s when I started going toward film.

‘I like to think I’ve taken over the family paparazzi role.’

Whilst sifting through decades of photos, Kara decided to focus on what she took in 2020 to encapsulate in a photobook, hopefully coming out at the end of this year.

‘It’s that classic artist thing, when you see a work of art and think, I could’ve done that. Yeah, you could, so why haven’t you?’

But Kara’s talents stretch past shooting on film, and into other mediums. After the look of panic in her eyes subsides after I tell her about Netflix’s Twin Flames documentary, Kara tells me about her burgeoning company, Twin Flame Creations (void of strange romance cults, thankfully).

With photographer friend Saskia O’Hara, the two have united their interest in the fantasy genre and are using multi-media skills to fill what they see is a gap in the market –

‘When it comes to the UK, oddly enough given the medieval and folklore tradition, there’s a gap in the market for content creation, especially with women behind the camera.’

Twin Flame Creations offer everything from, book cover images, bespoke photography, tailored video content, but also a space for people who just love fantasy and want to dress up and take nice photos.

Fantasy is absolutely having its moment, Kara drops the names of authors like Sarah J Maas, Rebecca Yarros, who’s exploding popularity and cult followings are representative of fantasy’s shifting place culture as we speak. From highly anticipated TV specials, the British Library featuring an entire exhibition just on modern manifestations of the genre, it’s hard to see how Twin Flame Creations won’t have appeal.

‘With all the multi-media avenues that people have to promote their work, we wanted to be able to offer that as well’.

Kara tells me she’s been meditating on the issue of her visa, ‘Whatever happens, happens.’

The threat of being sent back over the pond weighs on her. But whether it’s from here in thin the Big-Smoke, or back in the Midwest, I’m sure Kara Hakanson will have ‘exceptional promise’ to demonstrate in all her chosen fields